November 30, 2015

The Globe and Mail

By Richard Blackwell

As boomer business owners retire, transforming into a co-operative can be effective alternative

As hundreds of thousands of baby-boomers prepare to retire from the small businesses they own, most will overlook one succession option; converting their enterprise into a co-operative.

Many boomer-owners ponder transferring their companies to their children, or selling to a senior manager in the firm. Others are looking to outside buyers or even private equity investors. But transforming into a co-op – owned by the company's employees or even by its customers – can be an effective alternative, argues Peter Cameron, development manager at the Ontario Co-operative Association, an organization that promotes the formation of co-ops.

Unfortunately, the co-operative model is poorly understood, usually overlooked, and is completely neglected in most MBA programs, so it is not often considered as an option, he said. "The issue is just lack of awareness."

Shifting to a co-op can also work well for boomers who don't want to sell their business outright, but want to share the ownership burden – at least for a time, Mr. Cameron said. A founder can initially become a voting member of the co-op, and then be bought out over time by the other co-op members.

Credit unions – which themselves are cooperatively owned – are often willing to arrange financing for co-op members to buy shares. Payments can be deducted directly from pay cheques.

That was the model used by Careforce, an agency in Kentville, Nova Scotia, that provides home-base heath services in the Annapolis Valley. About ten years ago the organization's owner Lay Yong Tan decided he wanted to sell, and he brought in Peter Hough of the Canadian Worker Co-operative Federation to explore the possibility of having the care workers themselves take over.

While not everyone was keen – or had the financial resources – enough employees were willing to jump at the idea, Mr. Hough said. After a valuation was performed, a co-op was incorporated and several employees began buying the business through wage deductions.

After a year, the workers decided to accelerate the buyout. To help make that happen, a credit union in Halifax provided financing to the members who needed it, using the shares in the co-op as collateral. Within about five years, all the debt was paid off, and the company was running profitably. Currently, 20 of the 65 employees are owners.

This kind of model won't work in a large capital intensive business, where employees would have trouble raising the substantial funds needed, Mr. Hough said. But financing relatively small amounts for a service business is less of a problem, particularly if the firm is already successful. "From a financiers perspective, there is a lot less risk doing this than there is with a start-up."

Like any other business succession, the shift to a co-op model should be planned well in advance, and a proper evaluation must be performed. There also needs to be a detailed plan to transfer the previous owner's skills and expertise to the new owners.

Converting to a co-op also means the new owners must embrace a new role as key participants in the firm's governance. A democratic system, which usually involves a member-voted board, requires a "cultural mind shift" for people who were formerly just employees, Mr. Cameron said.

One reason a co-op structure is seldom considered is that there are many different models, causing confusion over terminology. A co-op can be a for-profit entity, with shares owned by members, or a non-profit where members are not directly share owners.

In some cases a business co-ops' members will not be its employees. In some circumstances a co-op can be formed by of the community where the business operates, or even by its customers.

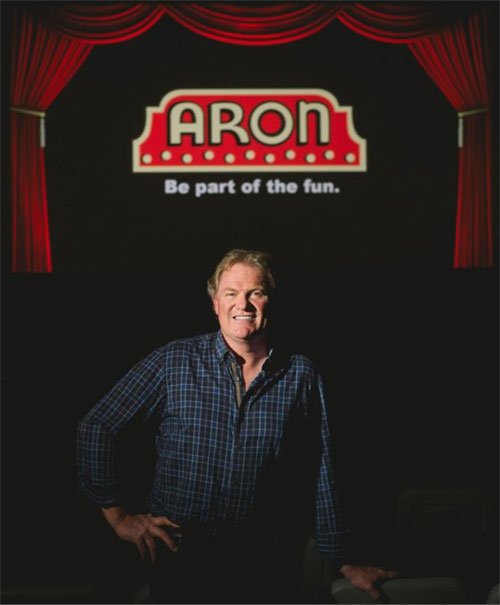

The Aron Theatre in Campbellford, Ont., for example, is a non-profit co-op owned mostly by members who live in the town, about 50 kilometres east of Peterborough.

Russ Christianson

Photo by Johnny C Y Lam

The movie theatre, constructed in 1949, was going to close in 2010 when its owner decided to retire. But Russ Christianson, a co-op specialist who happened to live in the town, figured he could set up a co-op to keep the theatre alive while providing the owner with an exit strategy.

Dozens of community members joined in, and bonds were sold to raise needed funds. The theatre itself has been revitalized, a new digital projector purchased, and first-run movies are bringing in new patrons. The co-op now has a surplus from operations, partly thanks to a lot of donated time from volunteers.

The co-op structure was the main reason the Aron survived, Mr. Christianson says, because it tapped into an emotional attachment of the membership to the theatre. "They didn't want to have another empty building on the main street," he said. "It is a community engagement project."

With so many Canadian small businesses owners ready to retire, Mr. Christianson is hopeful more will consider the co-op model. "Even if we got a small percentage of [companies changing hands] going to co-operative ownership, that would still be a large number."

Still, like other business transitions, a co-operative conversion is not a guarantee of success. That's particularly true if they are conceived during a crisis, said Mr. Cameron of the Ontario co-op association. He received desperate calls from workers at the Heinz ketchup plant in Leamington, Ont. and the Kellogg's cereal plant in London, when their closures were announced in 2013. They wanted help to set up worker co-ops to save the operations, but that was "too little too late," he said. "You want it to be a planned [event] so that people are making responsible decisions and you are passing over a good balance sheet."